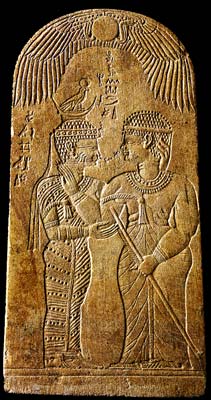

- Stela of Queen Amanishakheto and the goddess Amesemi carved from Sandstone. From Temple of Arum at Naga, late first century BC.

- The front of this round-topped small stela,

found between the fallen columns of the hypostyle hall in the Temple of

Arum at Naga is decorated in sunk relief of high technical and artistic

quality lender the winged sun-disc filling the upper fourth of the stela

two female figures are represented facing each other. Both are wearing a

close-fitting dress descending to the feet a fringed scarf over the

right shoulder, a broad collar and a round curled wig. Otherwise they

are represented in very different ways. The left figure has a slim

elegant body; the dress shows a title pattern of diagonal stripes and

dotted lines. A chin-band, an earring, an ornamented diadem with Uraeus

and a crown consisting of a pair of falcons with sun-discs sitting on a

crescent contrast with the pleated dress and the simple diadem of the

extremely corpulent woman on the right.

- The inscriptions in Meroitic hieroglyphs

identify the left figure as Amesemi, the divine consort of the lion god

Apedemak (the first complete reference to this name) and the figure to

the right as Amanishakheto (with out cartouche), the well-known Meroitic

queen buried in Pyramid N6 at Begrawiya.

- The goddess plays the active part: her right

hand supports the elbow of the queen's right arm. raised in adoration of

Amesemi; her left arm passes behind the queen. the left hand supports

the neck of the queen and a clotted line starting at the tip of the

forefinger, surrounds the head of the queen to her forehead. A chain

consisting of tiny ankh signs extends from Amesemi's nose to the nose of

Amanishakheto. This animation by the divine breath is illustrated in a

similar way in the reliefs of the Lion Temple at Naga.

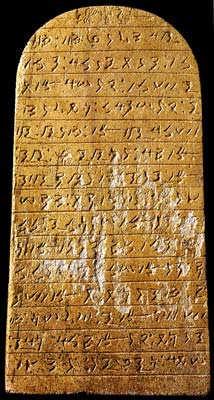

- The rear and the sides of the stela have

fifteen lines of text in cursive Meroitic, topped on the rear by a line

in Egyptian hieroglyphs without specific meaning. In his still

unpublished analysis of the Meroitic text Claude Rilly concedes a

'feeling of frustration' of the philologist in front of such a

well-preserved inscription but he succeeds at least in defining the

character of the text as a religious hymn.

-