Cistercian Abbey of Roche, South Yorkshire, England, is in the valley of the Maltby Beck, close to Doncaster and Sheffield. The site was enclosed by steep limestone cliffs and bordered on Bruneswald, later known as Sherwood Forest. This was a choice location for the monks: it provided privacy and solitude, as well as vital natural resources - water, woodland and stone.

Whilst the setting was solitary, it was not remote. It was close to several thoroughfares, within a few miles of the River Trent, and near to the castles of Tickhill and Conisbrough. The magnesium limestone cliffs that bounded the abbey on the north afforded shelter, and also an identity, for the community took their name from these rocky surroundings: the monks of St Mary of the Rock (Roche). Woodland to the east provided timber and fuel, as well as pannage for the pigs.

The Maltby Beck supplied water, an essential resource for the daily functioning of a self-sufficient community. Stone channels directed water through the precincts; it flowed from west to east, bisecting the site: the church, cloister and inner court lay to the north of the Beck; the abbot’s lodgings, infirmary and outer court to the south. Water was needed for a multiplicity of functions: drainage, cooking, washing, the cultivation of crops and the powering of mills; it was also used for liturgical purposes.

The nearby quarries provided a ready supply of high-quality stone, which was easy to work with and durable. Contemporaries admired the fine masonry at Roche, and stone from here was transported for use elsewhere, including Sheffield Castle and Windsor Castle. ‘Roche Abbey Stone’ is still quarried from here.

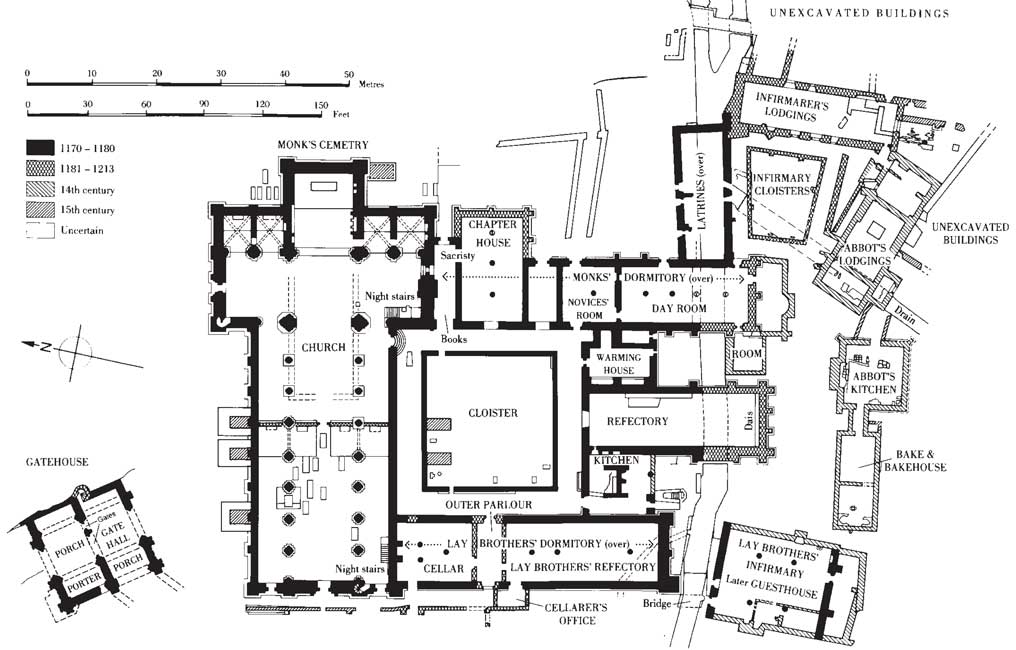

Plan (Goddard, 2000):

Roche Abbey was established in 1147 with land donated by Richard de Buili and Richard de Fitz Turgis, who also supplied an abbot and twelve monks. In the 12th century, stone buildings replaced the earlier wooden buildings on the site. Roche developed into a moderately sized Cistercian community of around 175 men compared to 600 at Rievaulx Abbey in North Yorkshire. By the 1170s the community had begun to establish a degree of economic stability and the monks started to extend their land ownership both locally and further afield. To do this they needed to borrow large amounts of money, and accumulated considerable debts. By the late 1180s, Roche was listed as one of ten abbeys heavily in debt due to over ambitious expansion. Like all abbeys, Roche experienced a marked decline in numbers as a result of the Black Death in the mid 14th century and by 1380, the community had been reduced to just fifteen, including a single lay brother. There was an increase in the numbers at the abbey by the end of the 14th century, and with renewed sources of income, many parts of the abbey were rebuilt and extended.

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, Roche Abbey was disbanded. There were 14 monks and 4 novices remaining, each of whom received pensions and 20 shillings towards new clothing. The site was confiscated by the Crown, and over the next two centuries, passed through a succession of private hands. There was a brief ceremony on 23 June 1538 in the Chapter House, and an orderly dismantling of Roche Abbey was planned. By the time this happened, local people had ransacked many parts of the abbey. Michael Sherbrook was a young boy at the time, and his family was present at the destruction. Some years later, he wrote a vivid account of the free-for-all pillage that occurred at Roche as at other abbeys:

"All things of price, were either spoiled, plucked away or defaced to the uttermost ... it seemeth that every person bent himself to filch and spoil what he could. Nothing was spared but the ox-houses and swincotes and other such houses of office, that stood without the walls."He tried to understand the motives for this destruction, and later asked his father why he had used some of the timber from the church, steeple and bell frame. Michael asked him why he was so ready to destroy and spoil the church which he had thought so well of. His father replied ...

"what should I do? Might I not as well as others have some profit of the spoil of the abbey? For I did see all would away; and therefore I did as others did"

Gatehouse and Inner Court: The existing gatehouse was the more important of the two original gatehouses, the outer gatehouse would have been on the site of the modern car park. This inner or great gatehouse was an essential part of the abbey to maintain seclusion from the outside world. Visitors were received here and directed to the appropriate part of the abbey. In the centre of the gatehouse are two archways, one wide enough for carts and the other for pedestrians. Visitors to the abbey could be directed straight through towards the church and abbey buildings or through the archway to the right for the outer court across the stream. Near the pedestrian arch a small doorway leads to the circular stair which gave access to the rooms above. These rooms served as the abbot’s offices for the administrative business of the abbey. The inner court beyond the gatehouse included the church and the main monastic buildings. There would also have been other buildings including guesthouses, an almonry (where alms were distributed to the poor and sick), storehouses, a bakehouse and a brew-house.

Church: The church was the most important building in the abbey and monks assembled here for between six and eight hours each day for services and prayer. The 12th century church is built on a simple plan, characteristic of Cistercian monasteries, with the entrance in the west end through to the nave (or main part of the church). The nave was divided by a wooden rood screen that carried a carved image of Christ on the cross. The stone base of this screen can still be seen. The lay brothers worshipped in the western part of the nave, where night stairs led directly to their dormitory. With the dramatic decrease in the number of lay brothers in the late 13th century, their part of the church was largely unused, so the wooden and stairs provided access to the cloister and the monks’ dormitory. This part of the church included the tower with the north and south transepts forming the cross shaped plan of the church. The transept walls are the largest remaining section of the church, and stand almost to original height. There are very slight differences between the architecture and stone carving of the north and south transepts. At the east end of the church is the site of the high altar and on nearby walls are the remains of aumbreys [cupboards] for storing the sacred vessels and sedilia [canopied seats].

Cloister: The cloister was a roofed arcade surrounding an open square. Monks spent much of their time here, working, studying and assembling for church or mealtimes. There were sheltered areas for reading and meditating, and facilities for washing near the refectory. Grouped around the cloister were the buildings that provided for the monks’ needs including the chapter house, refectory, kitchen, day room and parlour.

Chapter House: This was the administrative and disciplinary centre of the abbey where the community met each day. Chapters were read from the Rule of St Benedict and sometimes a sermon was preached. The building was designed with ranked benching around the room, to allow the monks to take part in the discussions, led by the abbot, about the economic and administrative business of the community.

Library/Sacristy: The sacristy was next to the church, here the vessels and vestments used in the church were stored.

Parlour: Conversation was forbidden in the cloister, but once a day necessary conversation was allowed in the parlour.

Monks’ day room/dormitory: The communal dormitory was on the first floor over the monks’ dayroom, which was used as a common room and covered workroom.

Reredorter [latrine] This two-storey toilet block was built over the stream and would have had wooden dividing walls and wooden seats. The monks had access from both the day room and the dormitory above.

Warming house: There are the remains of two large fireplaces in this room where fires burnt constantly from All Saint's Day (1 November) until Good Friday. This was the only warm space in the abbey for the monks to thaw out on chilly days in the winter. It may also be where hair and beards were trimmed and possibly manuscripts copied.

Refectory: This was the largest building on the

site, apart from the church, where the monks ate one meal a day

together. It was extended over the stream during the 13th century.

The abbot's table was on a raised platform (dais) at one end that is now

grassed over. The monks sat on the stone benches along the walls, some

of

the stone supports for the wooden tables survive. There was a pulpit

built on the west wall, where a monk would read from the bible whilst

the rest ate in silence.

Kitchen: Food for the monks and lay brothers was prepared and

cooked here. There is evidence of back to back hearths that were later

altered to create smaller hearths. here are openings through to the

refectory, one of which was a serving hatch.

Lay brothers' Range: On the west side of the cloister was the lay

brothers' refectory with a dormitory above. The dormitory had night

stairs into the

church. A smaller room in this range of rooms was probably the office of

the cellarer who had charge of all the abbey's supplies.

Outer Court: The outer court is the term used to describe the

area on the far side of the stream that cuts across the site. This is

where all the abbey's working buildings such as the mill, oxen houses,

stables, a smithy and tanneries were situated. There would also have

also been orchards, ponds, dovecotes and fruit gardens to provide food.

The buildings in this large area have not been excavated.

Monks' infirmary: This was where aged and ill choir monks were

cared for and spent their time if they were unable to take part in the

daily routine of the abbey. The infirmary had its own chapel, day room

and small cloister.

Abbot's House: As the status of the abbot was elevated in the

13th and 14th centuries, separate lodgings for the abbot

were built, away from the monks' quarters, with space to entertain

important guests. Adjacent buildings served as kitchen, bakehouse, and

brew house and may also have provided for the needs of the nearby

infirmary.

Lay brothers' infirmary: This hall was originally designed as the

place where old and infirm lay brothers were cared for. Later it was

partitioned into smaller rooms and probably used as a guesthouse.

Sources:

Goddard, L. 2000.

Roche Abbey, London: English

Heritage

University of Sheffield -

The Cistercians in Yorkshire

Project