Richard Parkinson is a curator with the Department of Egypt and Sudan in the British Museum and he said that "these are the greatest paintings we have from ancient Egypt," and "there is nothing to touch them in any museum in the world. Yet they were created for an official too lowly to have been known by the pharaoh. It is quite extraordinary." Parkinson's theory is that the artist must have been working on another project in the neighbourhood of Nebamun's tomb at the time. This building or burial complex would have been constructed, and decorated, on a far grander style for a far more important figure. Nebamun merely commissioned the artist and his team to 'moon-light' on this tomb.

As to their purpose, the paintings were intended to make Nebamun appear important in the afterlife. They would have covered the tomb's upper level, while his body was interred in a chamber below ground. Friends and family would have visited the upper part of the tomb, left gifts and held feasts to commemorate Nebamun's life - the paintings were not buried and hidden away but established a link between the living and the dead. Hence their importance to Nebamun's family. They were to be appreciated, leisurely, after the man's death as reminders of his achievements.

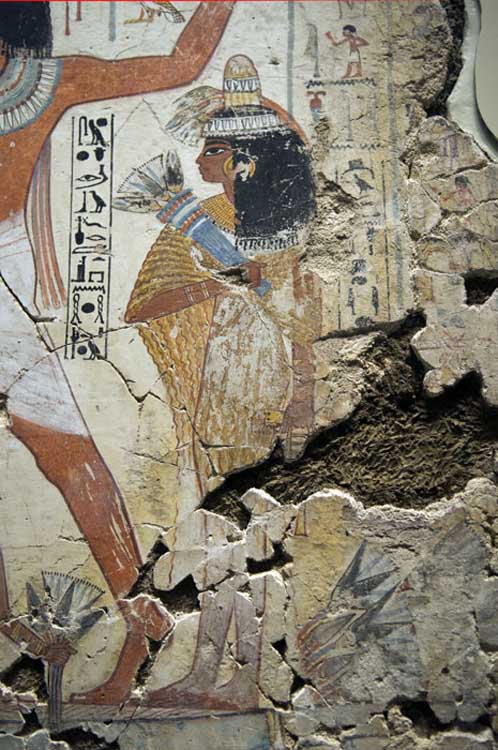

They were certainly not created at a leisurely rate, however, as Parkinson has found in his investigations of the paintings. Once the tomb's stone walls had been erected, they were covered in straw and Nile mud mixed together into a squishy paste. Then, when this was dry, a thin layer of white plaster was added. As that started to dry, the artist and his team began to paint, using soot from cooking pots, desert stones for red, yellow and white pigments, and ground glass for blue and green. Rushes, chewed at the end, would have acted as brushes. Squashed into the dark, narrow upper tomb, the painters would have had to work by lamplight before the plaster dried. The results are almost impressionistic in the freedom of their execution.

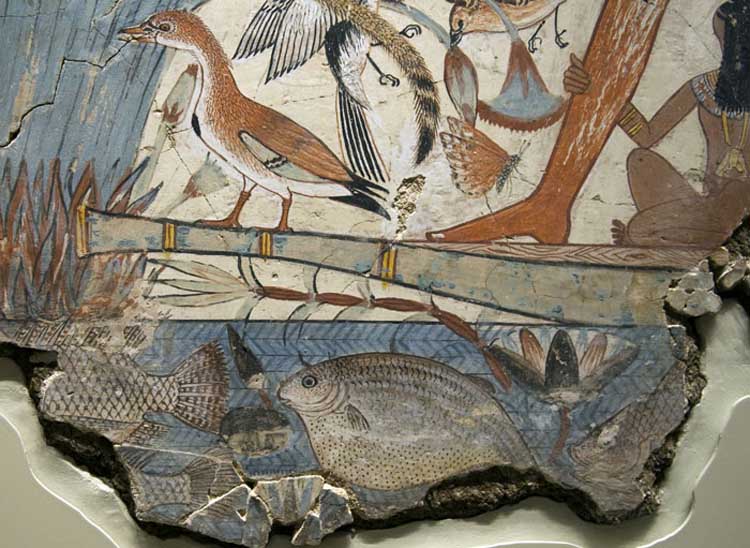

Objects and animals are often included because they had great symbolic importance. That great hunt scene is more than a depiction of everyday life: the birds and cat are symbols of fertility and female sexuality, and Nebamun's expedition can also be seen as "taking possession of the cycle of creations and rebirth", as one scholar has put it. Certainly, visitors should take care when trying to interpret the panels' meaning. The paintings repay detailed inspection. On several of them, you can see where d'Athanasi's grave robbers had started to crowbar a panel from a wall only to find it cracking, ready to split. They would then move on to splinter open the panel at a new spot; only sections that would appeal to British audiences were taken: the ones with naked dancing girls and scenes from gardens.

One or two other fragments did end up in other museums, including several that are now kept in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Evidence also suggests that a handful of fragments may survive elsewhere. For example, records from the Cairo Museum show that, just after the second world war, a few sections from the tomb were about to be exported from Egypt, a move that was opposed by its government - so officials had the panel pieces photographed and stored in the great vaults below the Cairo Museum. And that is where they rest today, though their precise location has been lost. All that is known is that among the tens of thousands of other ancient treasures kept in the museum's store, the missing Nebamun panels may be gathering dust in a dark, lost corner, or more likely have slowly decayed and are lost to history.